The dream of America, for most immigrants, is the dream of a better standard of living, earned through hard work in a country where employment laws apply to all regardless of race, gender, sexual orientation — or immigration status.

Equal treatment is a cherished American value. Legal protections must never be allocated on a sliding scale. When that occurs, the dream edges toward nightmare.

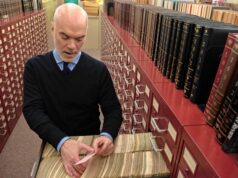

In the Gazette series “Under the Table,” reporter Amanda Drane and photojournalist Carol Lollis show how a group of restaurants have apparently flouted the law that serves as the bedrock of their employees’ standard of living — the minimum wage.

Massachusetts law requires restaurants to pay cooks, dishwashers and other untipped workers at least $10 an hour during the standard 40-hour work week. For hours worked beyond that, federal regulations supercede a state overtime exemption for restaurants and some other industries to require most establishments to pay time and a half.

Those laws protect not just American-born or naturalized citizens, but also the undocumented immigrant workers who arrived here from impoverished, unjust or violent homelands in search of a better life. Instead, Drane and Lollis found at least seven restaurants in Hampshire County where workers toiled as long as 72 hours a week and received a monthly lump sum that works out to as little as $6.50 an hour. Such restaurants — and many others throughout the Northeast — often find workers through job agencies in New York City’s Chinatown. Workers told the Gazette the agencies form the hub of an underground economy in which employers offer long hours and low pay to immigrants who believe they have no better option.

“At the beginning I started to feel like, ‘Oh, I’m undocumented, I don’t deserve [the minimum wage],’” said Lin Geng, a Chinese immigrant who worked 14 years in a variety of Asian restaurants before finally working his way up to a minimum wage position. Eventually, he says he realized, “I deserve that. Everybody deserves that.”

When asked about their pay practices, some of the restaurant owners defended them by saying that they also provide housing for employees. While some of those homes are clean and spacious, the Gazette found, others are cramped and poorly maintained. Workers at the now-shuttered Zen restaurant in Northampton said their employer-provided home on State Street featured bedbugs, cockroaches, and a non-working stove.

Even the best company housing doesn’t justify sub-minimum wages, labor officials told Drane. Employers can deduct no more than $35 a week from an employee’s pay for housing — a deduction that doesn’t close the gap between actual pay and the legal minimum in the cases detailed by the series.

Exploitive pay practices hurt workers first and foremost, but they also damage the majority of employers who are following the law and doing right by their staffs. Restaurants operate on thin margins, and owners who underpay workers gain an unfair advantage over honorable competitors.

Emalie Gainey, a spokeswoman for the office of the state Attorney General, told Drane the agency is “committed to protecting the most vulnerable workers in Massachusetts.” Carlos Matos, director of the Boston office of the U.S. Department of Labor Wage and Hours Division, added: “We seek to level the playing field for law-abiding employers.”

There are plenty such employers, including in the Valley’s Asian restaurant community. At Golden China Pan in Easthampton, for instance, owners Amy and Tommy Pan say they take pride in not only paying workers a legal wage but also in providing them with housing — even though such expenses can make it tough for the owners to pay their own bills.

State and federal officials are often hamstrung by the reluctance of underpaid workers — who fear loss of work or deportation — to come forward. When Drane and Lollis tracked restaurant workers to their employer-provided homes, many were reluctant to speak. Their American dream comes with an asterisk — the sense that they are not equal under the law.

The Gazette’s findings provide a starting point for state and federal officials to investigate the practices of these restaurants, and explore whether the pattern is repeated at other establishments.

In November 2014, allegations arose that female employees of the former Route 9 Diner in Hadley were routinely subjected to sexual harassment. The AG’s office, led by Maura Healey, responded by filing a complaint with the Massachusetts Commission Against Discrimination. The diner closed and four owners and managers were ordered to pay $200,000 in fines for creating “an unbearable and hostile work environment.”

In light of the findings of the Gazette’s “Under the Table” series, Healey and her federal counterparts have another opportunity to show they will fiercely defend the rights of all employees to fair and equitable treatment.