Alex Morse has a new pup — a goldendoodle that answers to Oliver. Can you say inseparable? The Holyoke mayor brought him home from Pennsylvania and claims that the quarantine has afforded him a bit more time to train the pooch. “It adds a bit of perspective,” says Morse. “The highlight of my day now is going to the dog park.”

A friend drove with Morse and brought back Oliver’s sister, Ava, too. Playdate heaven.

Morse’s counterpart in Northampton, David Narkewicz, has also been breaking in a new pup, Scout, a border collie, born at the same farm in Maine as his predecessors in the Narkewicz household, Skye, who died in 2019, and Chase, “literally our first born,” says the mayor, “Read: pre-children.” He and his wife, obstetrician Dr. Yelena Mikich, have raised two daughters — Narkewicz himself the stay-at-home dad for their early years. The mile-a-minute Scout, who just turned one, “has provided great comfort, laughter and exercise during the pandemic,” says Narkewicz.

Of the many issues the two mayors touch base on, in this, their last year in office, they might just be talking hound these days. “Narkewicz and I were joking, was it Truman who said ‘You want a friend in politics — get a dog?’” says Morse. “I shoulda got a dog nine years ago.”

They took charge of their respective cities at the same time, in 2011, one with years of experience in government, the other finishing up his senior year of college. One so boyishly young-looking his opponent in his first mayoral race imagined him in ads pedaling a bike with training wheels; the other just plain young, and gay.

One, the first mayor to call for legalized pot (Morse), the other the first to purchase it, a candy bar, which hangs in his office at City Hall, framed and under glass. “Break in case of emergency,” Narkewicz suggests.

Narkewicz grew up with eight siblings in rural Shelburne Falls, Morse with two older brothers in urban Holyoke, one of whom was lost to the opioid scourge a year ago this month.

Both were the products of hardworking parents who never went to college. Both retain some of the idealism that put them on center stage in the first place. Both announced they won’t seek reelection early, in order to give others enough time to mount a campaign.

A family’s influence

A framed photo, taken by longtime Gazette photographer (now retired) Gordie Daniels, hangs in WHMP’s Barbara J. Kuschka studio. It shows the two mayors, along with all the area’s other chief executives at a radio summit at Sylvester’s Restaurant. All are gone now. Greenfield’s Bill Martin stepped down in 2019, Amherst’s town manager John Musante died suddenly and tragically in 2015, and Mike Tautznik, the longest serving of the bunch, lost his wife Debra in a bizarre accident during Easthampton’s annual town celebration shortly after he left office at the end of 2013 after 17 years.

By this time next year, Morse and Narkewicz will also be out of the picture, driving home the notion that mayoring is a bit too 24-7 to be considered a lifetime position. Ten years, for most, is just about all you got in ya.

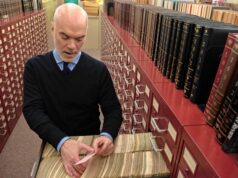

David Narkewicz, 54, got used to the late-night calls to the house long before he ran for office, thanks to his seven years as a top aide to Congressman John Olver, who retired in 2013.

“Uhhh … David?” Narkewicz recalls, in his deepest Olver impression, “and he’d ask questions about ongoing projects in the district. I drew on this training as mayor: You have to be prepared, you have to be able to speak off-the-cuff and you must be a quick study on a lot of different issues.”

But, about those nine kids growing up in Shelburne Falls?

“It was a different time in the United States,” says Narkewicz, the seventh born. “You could raise nine kids on a paycheck. My dad was a World War II vet, grew up on a farm, gave me my work ethic as I stacked wood into the dark hours of the night. As Clare Higgins (the former Northampton mayor he replaced) used to say, ‘The wealthy have servants, the working class has kids.’”

Though his mom had her hands full at home, she also got involved in all sorts of town boards, bringing about incremental change — more training for David. She lived to see her son inaugurated. “My sisters sprung her from Linda Manor,” he laughs.

Narkewicz has five older sisters, who were also his babysitters and earliest mentors, and if you think they didn’t play a big role in his development, particularly toward gender equality, you don’t know sisters. As he says, “The lens in which I view the world. The opportunities for women to advance — it hasn’t been a level field.” He takes pride in appointing the city’s first woman police chief (Jody Kasper), the first woman Department of Public Works director (Donna LaScaleia), and Merridith O’Leary, the health director, who he calls a “rock star through this entire pandemic.”

To shake hands with Narkewicz, you figure basketball, but he was actually among the shortest in his class. “I practically lived at Cowell Gym,” he says, “… any opportunity to play basketball.” He played point guard at Mohawk Regional; the height came after, exasperating his former coaches who wondered why he wasn’t 6 feet, 2 inches in high school.

He also describes himself as a class clown and gets a kick out of a story about Springfield Mayor Dominic Sarno’s supposed childhood vow: “When I grow up I’m going to be the mayor of Springfield!”

“I was not that kid,” adds Narkewicz.

A vision begins young

The kid in Holyoke, though, might have been. “I was always motivated in school,” says Morse, 32. “My mom would say ‘I don’t know where you came from.’ They met in public housing, my parents, had my brothers when they were very young, struggled out of poverty, and always encouraged me, made me see that if I put my mind to it the opportunities for me were limitless.”

But he entered Holyoke High as a self-conscious closeted teenager who felt out of place. Then, in his sophomore year, he told his parents that he was gay. “I came out at age 16,” he said, “My parents supported me, my community, my classmates, my school. I found I could navigate my world and the world around me with more confidence.”

For a kid who wanted to make a difference, Morse wasted no time. He founded the Gay Straight Alliance at the school, expecting no more than a couple of kids to show up. But 35 came and quickly became a force for change, Morse himself strongly speaking out against homophobic language in the hallways. “We started an alternate prom for queer kids. There was a lot of blowback. We were accused of trying to turn Holyoke into Northampton.”

But LGBT families were moving in. Things were changing, people were evolving, having difficult discussions, processing. “I fell in love with my hometown,” says Morse.

Even then, they joked about his future in the mayor’s office.

He ran to be the student rep on the School Committee. “That’s really where I found my voice,” says Morse, whose first image of the “one in charge” was that of former mayor Mike Sullivan, who is set to retire as South Hadley’s town administrator in June. “Mayor Mike was the mayor I grew up with, a mentor and a friend, who gave us a significant endorsement in 2011. When I was the school rep he used to say that ‘most kids who take this position complain about food in the school cafeteria, and Alex comes to these meetings to talk about how we need social justice and anti-bullying training.’”

Morse was the first in his family to go to college, Brown University, but he came home all the time. “So many of my classmates avoided going back to their hometown, but I always felt affection for this place. I thought what better place to give back, to use my education and life experience. I came back as soon as I could.”

He announced his candidacy for Mayor Elaine Pluta’s job at 21. “People said, ‘Well, it’ll be really good experience for you. So nice to see young people involved.’ But I was laser-focused.”

His fluency in Spanish lent legitimacy to the campaign. “We knocked on doors eight hours a day for months,” says Morse. “It made a difference. When you speak the language you can easily break down barriers between you and other people.”

But where did that confidence come from — nay, that audacity — to challenge an incumbent at 21, with the intent to win?

“Three other candidates running against the incumbent; I was the only one under the age of 60. We had the same faces in Holyoke government for decades, getting the same or worse outcomes,” says Morse. “I mean, we were 50% Latino but you’d never know it. There were forgotten neighborhoods. A lot of politicos told me to focus on the wards where turnout was highest. We rejected that and campaigned heavily in all wards.”

The “Old Guard” painted Morse as an outsider, but he soon found that the fabric of Holyoke was not a case of one thing or the other.

“I was born here, I went to school here, there is no one ideology of what being a Holyoker meant. My perception of Holyoke changed overnight. I think my age was more of an impediment than my sexuality.”

In all of Morse’s campaigns for reelection, it has been seen as Old Holyoke versus New, which is nothing like Northampton’s little Hamp versus NoHo rivalry of the ’80s — this is the real McCoy, Hatfields included.

“You look at some of our opponents’ headquarters and everyone looks the same,” says Morse. “You come to any of our campaign events and it looks like Holyoke … We opened the doors to City Hall. I would not have been reelected three times without the Puerto Rican community.”

When you first met Morse in 2011, you felt like you were shaking hands with someone vaguely mayoral, as in, not a 22-year-old kid. “I felt I had to dress the part,” Morse laughs. “If I’m asking people to vote for me to manage a $125 million budget and oversee a city with 2,000 employees — I almost wore a suit to BED! I’d never think of going to the grocery store in sweatpants and a hoodie 10 years ago. Now I do it all the time.”

A ‘policy wonk’ takes charge

Narkewicz, meanwhile, was not one of those who underestimated Morse based on his youth. “There are different paths that people take. When you run for mayor you’re basically saying to your respective city, ‘I’m the right person at this time to lead this city.’ He made that case.”

In his early 20s, Narkewicz was in the Air Force, stationed in Washington, D.C., “right under the Capitol Dome,” and couldn’t get enough of it. A political science major, he got involved with student government at UMass, then right back to D.C., working on the Hill, wonking out big time on public policy.

Northampton City Councilor Bill Dwight said, “I’ve always thought of David as a Boy Scout wonk, a workhorse, not a show pony, and that’s to Northampton’s benefit.”

Ironically, most of Narkewicz’ understanding of government came from his journey to Eagle Scout, and the politicians whose brains he picked on the way, like the late Congressman Silvio Conte, state Rep. Jay Healy, and then-state Sen. John Olver, for whom he would later work. “Brilliant mind,” said Narkewicz. “Graduated high school several years early, PhD at M.I.T. He gave you a political and public policy education you couldn’t get anywhere else.”

Fiscal stability has been Narkewicz’ hallmark, and he has tried from day one to stay years ahead.

“It makes tax dollars go further,” he says. “If your fiscal house is not in order, you could never do what we did in Pulaski Park (the downtown park was redeveloped). People always ask ‘why do we need all these reserves?’ I wish I could have thought to say a global pandemic.”

Mayors at ribbon cuttings get noticed, but what the public rarely sees are the issues that come shooting at you like lights in the subway. “Personnel issues, contracts, procurements, collective bargaining, so much minutiae, but I actually love the details,” says Narkewicz, “because (as established) I’m a wonk.”

“It can be a grind,” says Narkewicz. “You have to make sacrifices in your personal life.” His two daughters were in middle school when he first took office, “But they didn’t think of me as mayor — I was Dad. Didn’t matter what meeting I was in the middle of, ‘Dad, I need a ride home, ya gotta pick me up!’”

Once, while they were waiting for him in his office, they changed his screensaver to Hello Kitty. “That’s how seriously they took this high office I held.”

He met his wife on a blind date in D.C., where he was a Capitol Hill staffer and she was a medical student. “I wanted to meet someone not in government — it’s constant, you can’t turn it off,” says Narkewicz. “She was looking for someone not in medicine, and she was not super involved in the burning issues of the day. She has always been someone to talk to, a refuge from politics and controversy.”

Issues of the day

So, not to be controversial, but the Defund the Police movement? “Really important moment in national history,” says Narkewicz, who was one of only two mayors (the other being Somerville’s) to hang a Black Lives Matter banner at City Hall. “Some people were mad, the police union was mad, I was vilified. But we owe it to the Police Department that this be a thoughtful process. There are people who want to cut the department in half and divert the money to something else. This wasn’t created overnight. The idea that it can be deconstructed overnight and create something new — to do this correctly takes time.”

Neither mayor has ever hid from the media, but worry about the state of the press. “Less coverage makes it hard to stay in public service,” says Narkewicz.

Morse appreciates the Gazette dedicating a reporter, Dusty Christensen, to cover Holyoke, but his tenure as mayor coincides with the rise of social media, where, “Facts don’t matter. One person can post something false and incendiary and it’s the talk of the town.” That makes it hard for actual journalism to compete.

And about COVID-19, when it seems like Gov. Charlie Baker’s entire job is devoured by it, you recall that Narkewicz and Morse took office just as the famed October blizzard named Alfred gave the region a knuckle sandwich, slapped the grid into pieces, and turned all of us Jetsons into the Flintstones overnight. Dealing with COVID is like that, they will tell you, except it’s been going on since March. “It keeps you up at night,” says Narkewicz, “You think of the learning loss for kids, front-line workers putting themselves at risk; on every level it’s the most challenging thing.”

That said, the mayor has no doubts about people stepping forward to take his place. “It’s still a year away; hopefully we’re in a different place. Northampton’s had a long history of good leadership.”

As a former City Council president, Narkewicz relishes the inherent give and take between city’s executive and legislative branches: “It functions as a check on each other; it’s healthy. Challenges can happen when the mayor or Council tries to hone in on the authority or territory of the other.”

Morse has certainly lived it in Holyoke.

The needle exchange was a battle waged out of the gate in Morse’s first term. “We have the third highest rate of HIV and HepC in the state. It was the first program since 1995, the other being Northampton. We saw a big decrease in overdose deaths. It was exceptionally shortsighted on the Council’s part to try to block it … a program that saves lives.”

The life it couldn’t save was Morse’s older brother Doug, claimed by an overdose a year ago this month, at age 40. Morse from a young age watched his brother struggle, his parents with their sleepless nights.

“In and out of prison, detox, looks like he’s getting his life back together — many families have experienced this — suddenly the calls go unanswered, the phone is dead, he’s missing for days. My first year in office my brother gets arrested in Northampton — he went out and robbed a bank in Springfield. All over the news. I said at the time ‘I love him to death and will do anything to help him.’ I got more calls that week than any other time, for speaking about it and trying to break the stigma.”

During Morse’s congressional run, Doug Morse was in a program in Pittsfield. He had a good job and would join his brother for events. “He walked around with me. We ran into the mayor of Pittsfield — ‘This is my brother Doug.’ He thanked me later. ‘You make me feel normal, like you’re proud of me.’ Which allowed me to see how he feels about himself.”

“Then he went missing and you get the call you never want to get. He was always able to text me when he wanted to get picked up, and we’d get him a bed somewhere. I saw firsthand how difficult the system is. When he died, old roommates in rehab, even cellmates, called to say what a good guy he was, how he encouraged everyone in recovery to stay positive.”

Doug left behind a son, Gavin, who “he loved to death,” says Morse. “My mom used to plead with him: ‘Is your son not reason enough?’”

But heroin knows no reason. A coiling python with an insane grip, long, after the initial euphoria fades.

Morse’s sexuality, and the way he was embraced by a good part of the community, may have caused him to take certain things for granted. But that sexuality got called into question during last year’s bid to unseat Congressman Richard Neal and his sizable war chest. Neck and neck a month out. Fundraising through the roof. Then the UMass College Democrats. The dating sites. The Daily Collegian, running the planted story the main news outlets rejected. The insinuations. The salacious allegations. The adjunct professor — gasp — preying on students, none of whom filed any complaints.

The conspiracy seen for what it was only after tens of thousands had voted early. “It really hurt,” said Morse. “One in five in our polling said they were less likely to vote for us.”

He calls it the worst weekend of his political life.

“I called my dad that Sunday and told him I was going to be dropping out that afternoon. I met with my team and told’em I was out. In the course of two hours we were in that room the statement changed from ‘I’m dropping out’ to ‘I’ll see Congressman Neal on the debate stage next Monday.’ Thousands of people reached out that weekend sending solidarity, young people, queer people, this wasn’t about me.”

The future

Though bitter about the way the campaign ended, Morse does not rule out another statewide run, but, like Narkewicz, has no immediate plans.

“We all have a shelf life in politics,” Morse says. “This job … it’s a thankless job, did I say that out loud? Most difficult job in politics. You negotiate, make budget cuts, say yes sometimes and more often times no. And you’re not just a manager, you’re also a public figure, which means you’re only there if you get 50% plus one.”

As we’ve discussed, 10 years is a pretty good stretch for those in the mayoring trade.

But about that search for love — has anything gotten, well, serious?

“In short no, though it did at one point during my mayoralty, but things happened,” says Morse. “At the moment it’s just me and Oliver. Sometimes, with the job I have, I appreciate coming home and it’s just me and the dog. But I’m optimistic.”

He just turned 32. “I’d love to meet someone and start a family,” he says, recalling the special bond he had with his late mom Kim, that love shared between parent and child. “I do want that someday.”

Way up in the bell tower on top of Holyoke’s centuries-old City Hall, there is a powerful view of the entire city, one of those places mayors have keys to. Morse can point to his old neighborhood off Sargent, to the housing projects his parents grew up in, to the Canal Walk he championed, to the parks where he played every sport offered before settling on tennis in high school. The city’s paper mill legacy is still visible through the clouds like the Parthenon, but revitalization, part of Morse’s legacy, sprouts in all directions, particularly with cannabis cultivation.

“People from all over are investing in the city,” says Morse. “We’ve granted more licenses than any other town or city in the state.”

Anyway, if you’ve got it in you to make the rickety wooden climb up an endless pattern of steps and tight corners, you’ll finally see the giant old bell, the gears and workings of the soon-to-ticking old clock, and a view to take your breath away. A good place to go, it would seem, to think things out.

For Narkewicz, thinking time occurs in the woodsy meanders of Mineral Hills or Fitzgerald Lake. “One of the things that makes Northampton special to me is that you can be in the heart of a vibrant, bustling downtown one minute but then a short 10 minutes away you can be hiking a hillside trail with no one around you except trees, wildlife and the silent beauty of nature.”

And the snuffling exuberance of a dog, close by, it goes without saying.