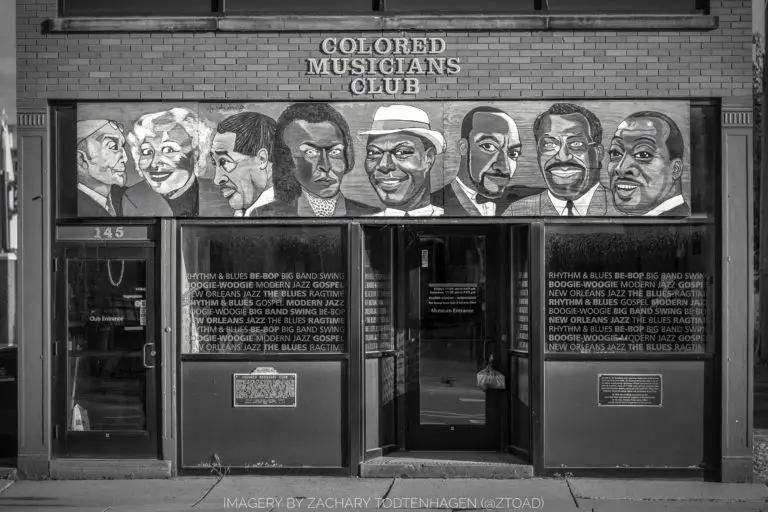

In Western New York, you’ll find plenty of music history, but none so unique as the Colored Musicians Club in Buffalo, on the edge of Willert Park. The only Black-owned and operated music club of its kind in America, the venue has played host to a bevy of jazz musicians since the 1920s, including John Coltrane, Duke Ellington, Billie Holiday, Allen Tinney, Elvin Shepard, Boyd Lee and Frankie Dunlop, Dodo Greene, and more. The historic venue continues to make history, as well as preserving the rich cultural heritage contained within.

History

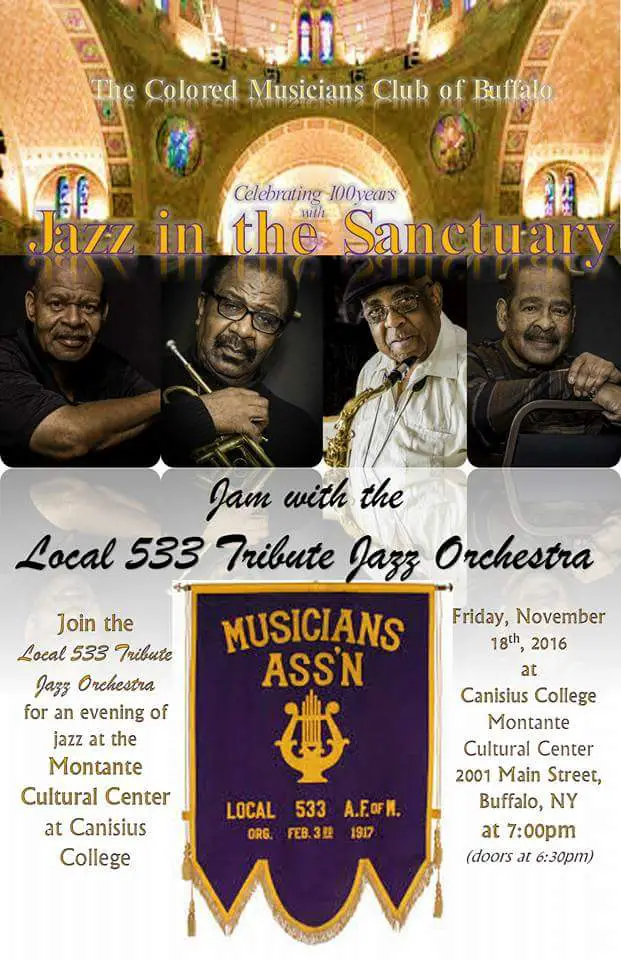

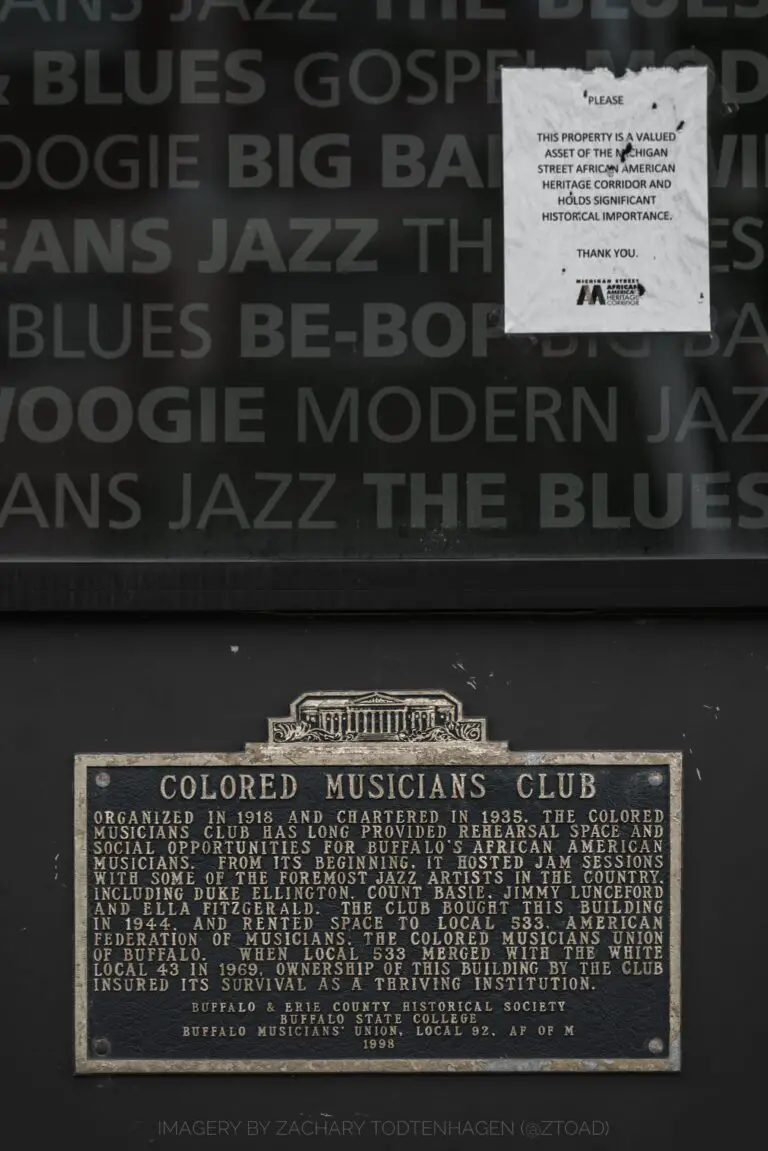

The club’s origins are found in Local 43, a chapter of the American Federation of Musicians. The all-white union refused to allow African-American musicians to join, and thus, a separate union chapter, Buffalo Local 533 was formed on February 3, 1917. This made Buffalo the eighth city in America to have racially segregated musicians unions.

In 1918, a group of members of the union formed a social club, where musicians were able to hang out after finishing their jobs at night, according to charter member and then-President of Local 533, Dr. Raymond E. Jackson. For 25 cents, members could get a ‘a trotter,’ consisting of a plate of pork, a pig foot, a plate of beans and a bottle of beer. Sundays were practice days and band rehearsals, using the club’s piano and free space – their space.

The Colored Musicians Club would find a permanent home at 145 Broadway in 1934, after being housed in the union headquarters on Michigan Avenue, at 96 Clinton Street at the corner of Oak Street, and the Masonic Temple at 168 Clinton Street. Originally a vacant storefront, the building at 145 Broadway was constructed between 1880 and 1900 and initially housed Charles Zifle’s boot shop, followed by a cigar and tobacco stand owned by Michael McNamara, then a billiards parlor, several union locals, and the Niagara China and Equipment Company.

Incorporated on May 14, 1935, the club had space upstairs for practice, rehearsals, and performances, while downstairs the union would hold meetings. The club was a separate entity from Local 533, and provided members a sense of community outside of their professional and family environments. Its purpose was stated as follows in its certificate, and consequently in its Constitution, which in part reads:

[To] foster the principles of unity and cooperation among the colored musicians of Erie County, N.Y.; to develop and promote the civic, social, recreational and physical well-being of its members; to improve and enhance the professional and economic status of its members; to stimulate its members to greater musical expression; to encourage and develop a fuller appreciation of music on the part of its members and the public; and generally to unite its members in the bonds of friendship, good fellowship and mutual understanding.

Notable members of the Local include Louis Armstrong’s wife Lucille and Aretha Franklin.

A Relic of a Bygone Era

George Scott, president of Buffalo’s Colored Musicians Club, and leader of the George Scott Big Band, said in an interview with NYS Music that the venue is “still current, not obsolete,” noting that an extended family exists within the confines of CMC, always a home to musicians and patrons alike.

CMC is not only Black-owned and operated, but the building is owned as well, setting it apart as the only national venue of this nature. Following integration in the 1960s, African-American locals in other cities would lose real estate when merging with the larger, more powerful white Locals. The separation of the Club from the Local would allow Colored Musicians Club to stand apart and allow African-American musicians in Buffalo a place to call their own.

In 1979, the Club was granted historic landmark status, and 20 years later, was designated as a historical preservation site. Thus, there is an astounding history at this venue which has not moved from its location on Michigan Ave. for more than 85 years.

Location and historical significance

Situated as the largest city in Western New York, Buffalo is in close proximity to Pittsburgh and Cleveland, as well as a gateway to Toronto. Thanks to the railroads and the Great Lakes, Buffalo was a natural center to gravitate towards. Making it easy to get to Buffalo meant musicians had easy access to audiences, as well as jobs in factories. In fact, many jazz musicians who migrated north to Buffalo would find work during the day in a factory and clubs to play in at night.

Buffalo has been a gateway to the Midwest, North and Northeast, well before the Colored Musicians Club opened its doors, thanks to the Erie Canal. In additiion to being in a key geographic location for commerce, the Queen City harbored stops on the Underground Railroad. Across the way from CMC, the Michigan Street Baptist Church served as a stop on the Underground Railroad, allowing for safe passage into Canada for those escaping slavery in southern states.

Michigan Ave. would later become the home to many jazz clubs, all gone now, save the Colored Musicians Club. During Prohibition, speakeasies would be found in the area, and those looking for jazz knew where to find it after hitting a speak.

Even though there were lean years in the 1960s, 70s and 80s, membership of the Club remained strong as the demographics of Buffalo changed. The area around CMC started to become blighted, with shuttered businesses peppering Michigan Ave. and Broadway. Thus, locals would not venture into this part of town, but the Club persevered and still stands today.

Integration > Racism

While ‘The Club’ has origins that pre-date World War Two, and tied to a lack of integration and institutionalized racism that followed, the club itself was the first to allow integrated bands and audiences in the 1930’s and 40’s. Inside the doors to the Colored Musicians Club, there was no racism and no racial disparity, and no racial unrest outside the doors. Even the Black Lives Matter protests of 2020 were far removed from the club, a haven for integration of musicians and audiences alike.

During the 1950’s, jazz bands were becoming more racially integrated, and was a positive step for race relations in a country on the cusp of Brown v Board of Education and The Civil Rights movement of the 1960s. However, racism would find opportunities to rear its ugly head, beginning with the power and size of African-American Locals, compared to their white counterparts.

In 1964, American Federation of Musicians President Herbert Kenin told the segregated Locals that the Federation was required to desegregate or be in violation of the Civil Rights Act, effective July 1, 1965. Locals 43 and 533 merged on January 1, 1969, renamed as the Buffalo Musicians’ Association, Local 92, A. F. of M. But racism did not end with the Civil Rights Act’s passage. The new Local had a preference for White musicians, putting Black musicians out of work. The advantage here though was that the Colored Musicians Club was owned outright by Club members, giving them an advantage not found elsewhere – an assured location at which to perform.

Among musicians, there is a certain kinship that prevailed and prevented racism from gaining a foothold. CMC is a sacred place to come together at the club, regardless of ethnicity.

Legacy and Influence on Buffalo today

Today, as it was more than 85 years ago, the Colored Musicians Club was a humble brick building that served as a sanctuary for musicians. The history of the room unites performer and patron alike.

The influence on Buffalo is particularly educational. Lessons with revered jazz musicians have been offered at CMC for decades, and those who come for lessons can be found at Jam Night on Sundays, allowing these students of jazz to sit in with musicians, thus reinforcing The Club’s original intent and drawing in new blood. Here, youth see what they can become when given the opportunity.

There have been countless musicians at all levels of playing who have walked through the Colored Musicians Club doors since 1935. Among them are Billie Epstein, who hosted a jazz radio show at the venue; Stuff Smith, a jazz violinist who would go on to play with Count Basie; jazz pianist Diana Krall (via Toronto) who played at jam sessions and is married to Elvis Costello; sax player James Brandon Lewis; Zuri Appleby, bassist for Nick Jonas, Lizzo and Adam Lambert; drummer for Beyonce, Venzella Joy; and Carmen Intorres, who started taking drum lessons at club when he was younger, and is now located in New York City.

George Scott notes that not only do musicians come to the club for music and a taste of history, but sometimes unexpected visitors drop by. The late Chadwick Bosman stopped by the club on a day off from filming Marshall. Scott met him when he came to the club, showed him around the museum and educated him on the history of the venue. A year later, he was Black Panther and George made the connection.

The Future

The Colored Musicians Club will reinforce its educational commmittment with a new addition being installed over the course of 2021. A second floor with an elevator and a rear entrance – thanks to New York State funding – will ensure accessibility for all, as well as classroom and lecture space, allowing for music to be taught daily above the club.

The Club will also expand into the adjacent parking lot, allowing for larger events and audiences, as well as Sunday night Jam Sessions. As noted by WNYHeritage, additional expansion plans include a spectacular two-story atrium, a well-appointed “Artist Green Room,” chic decor and a more prominent stage with an enhanced lighting plan, including fixtures and infrastructure.

While there are no live events for the near future, CMC has a museum located within the building, an engaging space for all. With a multimedia archive stretching across the history of the club, patrons can learn about milestones of the club, with tickets only $10 or less for tours Thursday through Sunday, 11am-4pm.

As we wait for live music to return to all corners of the Empire State, those curious about CMC have videos, virtual performances and virtual tours available to them through the website and Facebook page. Long live the Colored Musicians Club.

The post Buffalo’s Colored Musicians Club: the Last Venue of its Kind appeared first on NYS Music.