In March 1962, NASA Administrator James Webb addressed a two-paragraph memorandum to NASA Public Affairs Director Hiden T. Cox about the possibility of bringing in artists to highlight the agency’s achievements in a new way. In it, he wrote, “We should consider in a deliberate way just what NASA should do in the field of fine arts to commemorate the … historic events” of America’s initial steps into space.

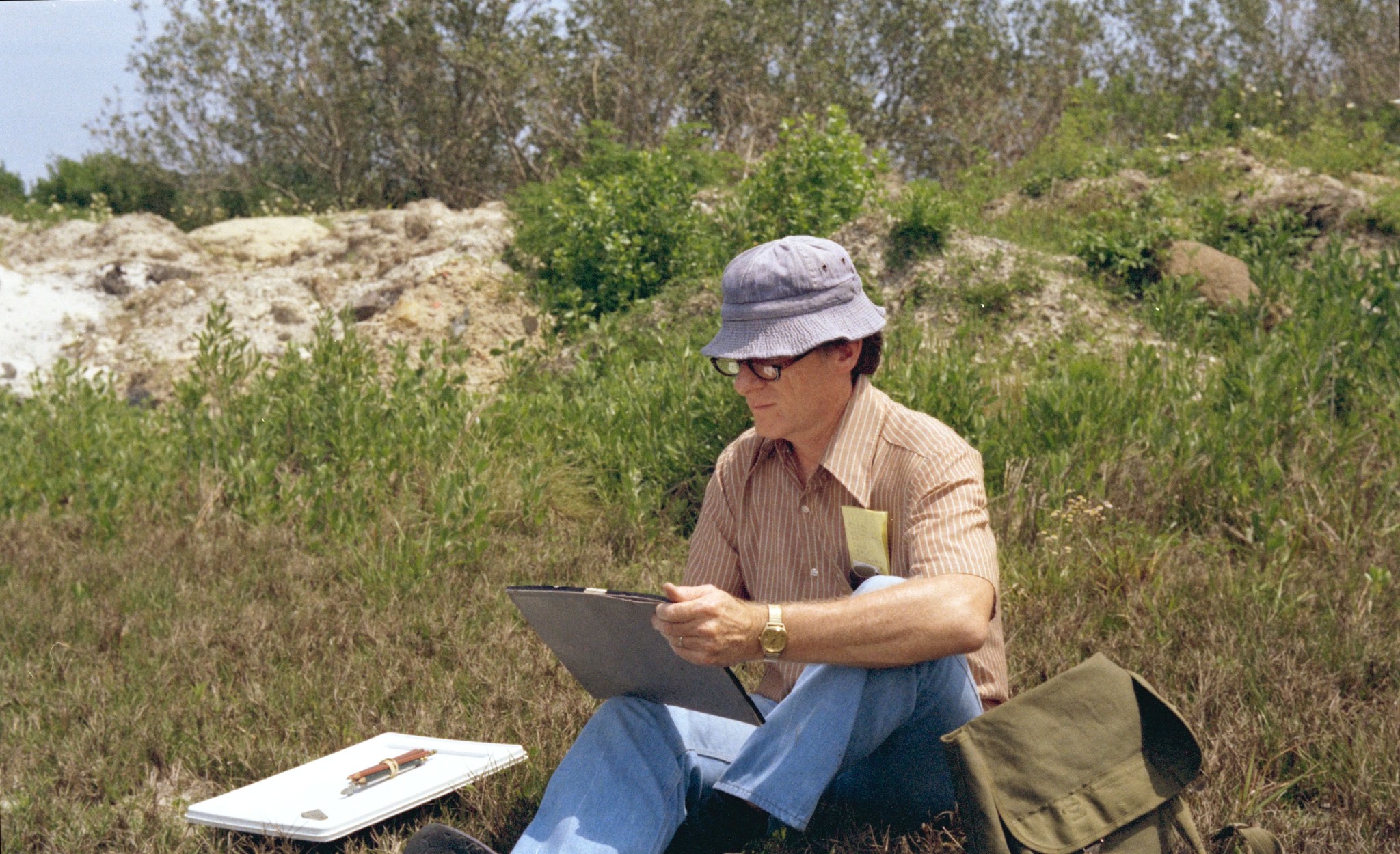

Shortly thereafter, NASA employee and artist James Dean was tasked with implementing NASA’s brand-new art program. Working alongside National Art Gallery Curator of Painting H. Lester Cooke, he created a framework to give artists unparalleled access to NASA missions at every step along the way, such as suit-up, launch and landing activities, and meetings with scientists and astronauts.

“It’s amazing just how good a sketch pad is at getting you into places,” Dean said in a 2008 oral history interview. “People shy away from cameras, but sketch pads, pencils, paints, you know … a lot of doors got opened that you could never open by making an official request.”

The NASA Art Program selected an initial group of eight artists – Peter Hurd, George Weymouth, Paul Calle, Robert McCall, Robert Shore, Lamar Dodd, John McCoy, and Mitchell Jamieson – in May 1963 to capture their interpretations of the final flight of the Mercury program, Faith 7. Seven of these men spent their time exploring Cape Canaveral and covering prelaunch activities; Jamieson covered splashdown and landing by being assigned to one of the recovery ships.

Though the grants and honorariums associated with being a NASA Art Program participant were always nominal – $800 in the 1960s and up to $3,000 in the early 2000s – many other well-known artists continued to work with the program through the decades that followed, including Norman Rockwell, Robert Rauschenberg, Andy Warhol, Annie Leibowitz, and Chakaia Booker.

“It wasn’t money they were after,” Dean noted. “They were interested in the experience and being invited back into where history was being made. I mean, artists have been with explorers … [since] the early days of exploration in this country.”

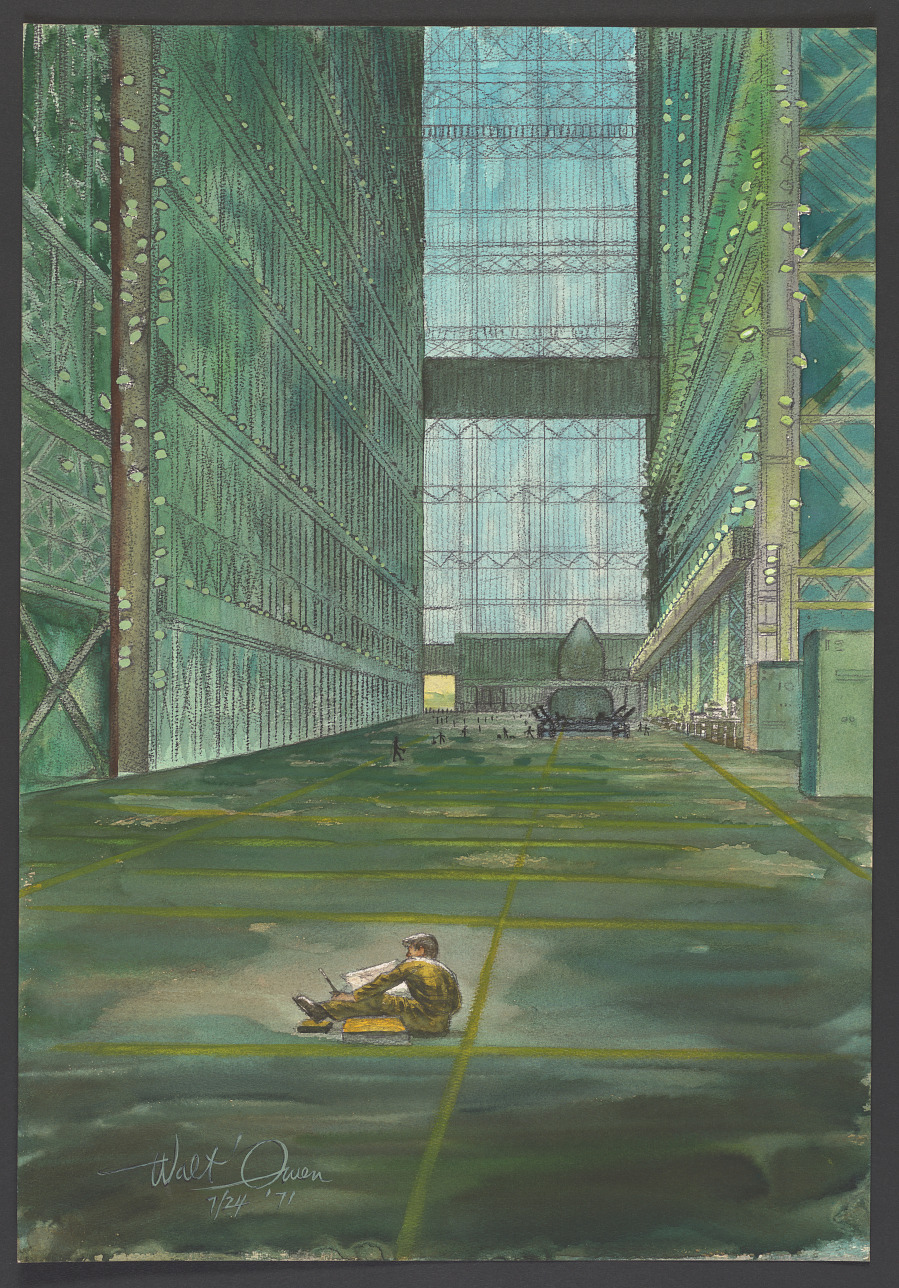

Dean also recognized the importance of having a diverse range of artists present, even if they were all ostensibly there to capture the same historical event. “When you have six artists sitting together painting the same thing,” he explained, “each painting is different. And that’s because … they’re seeing all the same thing, but the image goes through their imagination too and all their experience.”

While there were some initial concerns about the NASA engineers and scientists accepting the artists as a new, prolonged presence in their midst, Dean found that once they “let the artist in and see what they were doing, they really hit it off because the engineers and the scientists and the artists really use a lot of imagination. So they were really connecting on a certain level.” He also observed a unique symbiosis occurring between artist and worker: “When an artist … turns your workplace into a work of art, you know, it validates everything you’ve been doing. It is a real motivating factor to see something like that.”

Dean served as the director of the NASA Art Program from 1962 to 1974, before leaving to become the first art curator for the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum from 1974 until his retirement in 1980. He passed away in Washington on March 22, 2024, at the age of 92. But his legacy lives on in the NASA Art Program collection, which currently has some 3,000 works divided between the National Air and Space Museum and NASA. Today, the program is focused on STEM outreach initiatives to inspire youth through creative activity.

To learn more, check out selected works from the NASA Art Program on the NASA History Flickr page and the National Air and Space Museum page.