The year is 1978, and a new musical movement is bubbling up from Manhattan’s seedy underground. New York City as a whole is in a state of constant decay. Unemployment and crime have increased to record highs, and smog clouds the skyline. For many, the city has become a no-man’s land, as almost a million leave the boroughs. Despite this, downtown Manhattan becomes a haven for Bohemians and artists from around the country. It is these artists who spearheaded the No Wave movement.

No Wave is a movement that defies labels and genre. On one hand, No Wave built off the DIY ethos of Manhattan’s punk scene that had emerged only a few years earlier. However, No Wavers hated the derivative nature of punk, and wished to push boundaries even further than their predecessors. No Wave does not have a unified sound, with different bands incorporating disco, funk, jazz, and noise. While having diverse sounds, nihilism and a desire to break boundaries unified all of these bands.

Manhattan in the 1970s

By the start of the 1970s, New York City was in a state of dire economic crisis. In 1970, The New York Times reported that unemployment had increased by 41%, leaving 300,000 without work. These statistics, while being the worst in NYC’s history at the time, would only worsen through the decade, rising to 12% in 1975. As the city’s economic state worsened, many middle class white families fled in a process known as “White Flight.” Throughout the decade almost 820,000 people left for the suburbs, with the Bronx’s population even falling by 30%. This exodus only further eroded New York City’s tax base, worsening its economic woes. This economic crisis came to a head in 1975 when the city nearly defaulted on its debt. In an attempt to cut costs, city officials slashed many social services. Police officers and teachers dropped by 6,000, and firefighters by 2,500.

“It was like somebody escaping from the Warsaw ghetto and saying they’re killing people there. Nobody believed it.”

– Ed Koch, Rep (D-NY)

With the economic collapse of New York City, crime rose to record levels. By 1979, there was an average of 250 felonies committed per week on the New York City subway system, with the overall crime rate being 3 times higher than today. As desperation increased, many turned to prostitution, with over 2,400 arrests occurring in 1976 alone. For many the greatest metaphor for these dark ages was the July 13, 1977 blackout. At 9:34 PM, New York City went completely dark, leaving 8 million without power. For the next 25 hours, chaos consumed the city. There were over 1,000 cases of arson, and people looted over 1,600 stores across the boroughs. As novelist Ernesto Quinonez recalled, “It felt like some sort of bomb had gone off… and all you had was a whole bunch of confetti and paper. [The city’s] frustration had been released.”

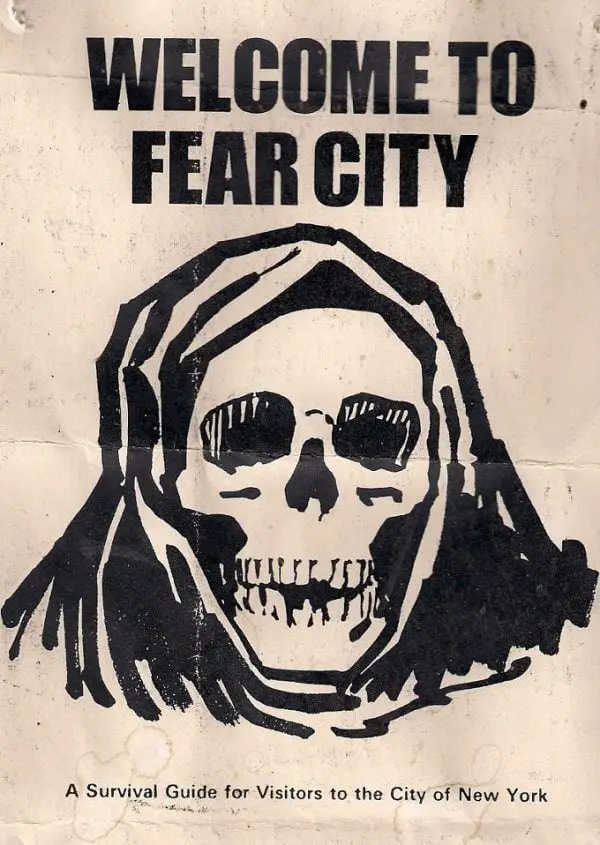

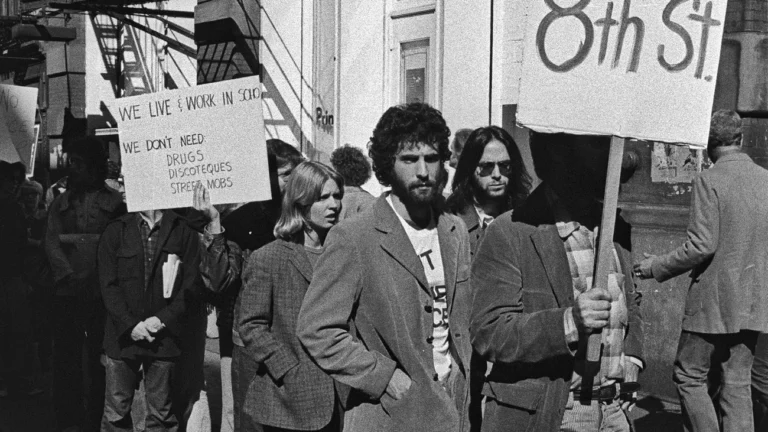

The external view of New York City was awful to say the least. NYPD officers began referring to the city as “Fear City,” playing off of rising crime rates- a phenomenon not unique to NYC during the 1970s. This reached the point where people even handed out Fear City survival guides at NYC’s airports, which featured a large image of the grim reaper on the cover. Media portrayal of the boroughs as a dystopian wasteland only worsened this image. Movies like Death Wish (1974) where Charles Bronson plays a vigilante taking revenge on muggers who assault his wife and daughter in Manhattan.

While many fled the city, many young bohemians began to flock to Manhattan, forging a new arts scene. Some were attracted by the graffiti and trash-littered streets and subways, and the idea of “slumming it” in the city. Others, however, had much more practical motivations in moving to the city. As Mark Cunningham of No Wave band MARS stated, “Cheap rents enabled a whole generation of artists to move there after school and not have to do too much slave labor to pay the bills.” Rhys Chatham of the band the Gynecologists adds on, “I had a 1200 square-foot loft for $180 a month.” These low rents, and proximity to other like-minded young people, allowed Music to flourish in New York City.

“All the ‘straight’ people were trying to get out of New York, but all the freaks… we were trying to get in.”

– Maripol, Fashion Designer

Emerging Music Scenes

During the 1970s, New York became a hub of musical innovation, drawing from diverse influences. Most importantly for the development of No Wave was punk rock. Throughout New York City, young people were growing increasingly fed up with musical trends. As legendary singer Joey Ramone remembered, “We were a reaction to all the pretentiousness and clichés and all the bullshit. It was at the beginning of disco, the beginning of corporate rock, like Journey, Foreigner, all that shit. You know, five or six tracks on an album, 45-minute guitar solos or drum solos.” As a result of this, punks looked back to a simpler time of rock and roll, with loud fast riffs and short songs.

Punk was as much a reaction to the social ills of the city as it was a reaction to musical cliches. As publicist Mitch Schneider stated, “New York punk was great because it sounded like the city. It was tightly wound, really urgent, and New York sucked at that time.” Punks wanted to make music that was “real” and reflected their experiences living in the boroughs. As a result songs tackled issues like drugs, violence, and decay. Sonny Vincent of the Testors remembers, “Graffiti everywhere, garbage, violence, drug deals on the street. You name it. But it was ours.”

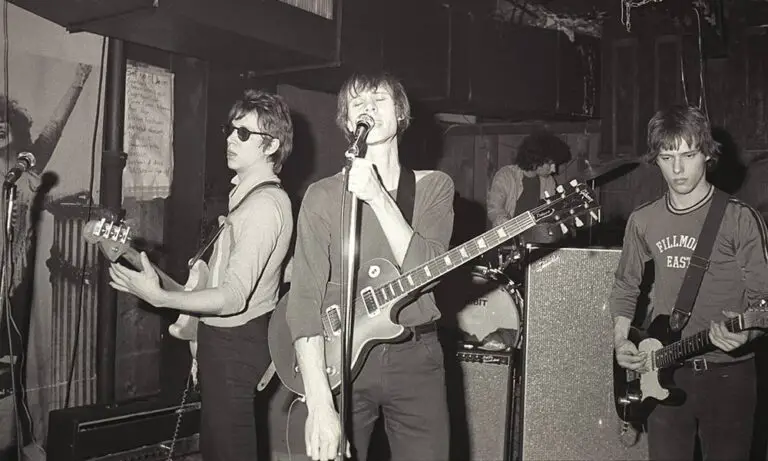

The simplicity of punk did not last long. As soon as it began, bands like Television began to experiment with structure, and instrumentation. The CBGB regulars, much to the chagrin of punks like Joey Ramone, proved that punk too could be “pretentious” with long solos, and varied lyrical themes. Bands like Television formed the “post-punk” genre, a more artsy, experimental outgrowth of New York’s punk rock movement. New York’s position as a cultural hub aided in this musical innovation. Touring acts like Cleveland’s Pere Ubu performed in Manhattan, deeply influencing future no wave artists. As Musician Rick Brown recalls here’s a “guy yelling and banging on a piece of metal and there’s a guy twiddling knobs and making weird sound.” Performances like these illustrated that punk could be so much more than just three chords and a lot of energy.

“Hell found potential in nihilism, in the void left after everything’s rejected. Like the abandoned city the no wavers flocked to, his ‘blank’ wasn’t empty or futile, but rather an open canvas offering a road to rebirth. No Wave would take this concept and run with it.”

– Music Historian Marc Masters,

on Television bassist Richard Hell

As much as No Wave was indebted to punk, it was also a direct rebuke against many early punk bands. Many early members of the No Wave movement were young visual artists, attracted to Manhattan by its avant-garde scene. Because of this, many of these musicians wanted to push the definition of what music was, rather than rely on past influences. As legendary No Wave singer Lydia Lunch once said: punk was nothing but ““sped-up Chuck Berry riffs.”

Adding to this distaste of punk was the growing commercialization of the genre. While punk had begun in the underground, it had soared to the top of the charts by the end of the 1970s. Punks began incorporating aspects of modern rock and pop, forming a new genre that came to be known as “New Wave.” Bands like Los Angeles’ The Knack and New York’s Blondie reached Billboard’s no. 1 spot with their pop-influenced New Wave tracks “My Sharona” and “Heart of Glass.” Many members of New York’s avant-garde wanted to stand in direct opposition to the mainstream-ification of punk, and create a new movement that was explicitly anti-commercial.

In tandem with the rise of punk, a new genre of dance music emerged from Manhattan’s gay club scene. This genre – dubbed disco – erupted as people moved to the dance floors to forget their worries. With simple 4/4 beats and four on the floor rhythms, anybody could join in. While large clubs, like the famous Club 54 existed, much of disco was spread through independent DJs, sometimes holding concerts in their lofts. Possibly the most famous of these DJs was David Mancuso. At a legendary February 14th, 1970 loft party, Mancuso mixed R&B, psychedelic, and world music for his guests. This event attracted not only dancers, but also rockers, beginning a chain reaction that would lead to the eventual incorporation of dance elements into punk just a few years later.

The Start of No Wave

Drawing from such varied influences, No Wave is often very difficult to define. Some bands’ sounds have little to nothing in common with each other. Some groups play straight jazz, others pure industrial noise: so how did they become grouped as one cohesive movement? One thing all No Wave bands share is their attitude: unashamedly experimental and nihilistic. Much of this attitude already existed in Manhattan’s avant-garde scene, but were only further honed by this new movement.

Starting with groups like the Velvet Underground in the 1960s, Manhattan became a hub for boundary-pressing artists. The avant-garde scene of Downtown Manhattan was an extremely close-knit community, with music and visual arts spread by word of mouth, and displayed at shows in artists’ private lofts. This scene, much like the later No Wave movement, combined extremely disparate styles all united by a desire to make something completely new.

For some, this avant-garde mission took the form of classical music. Following his graduation from Mills College in the early 60s, Steve Reich returned to his native Manhattan to pursue composition. Reich, while classically trained, wanted to redefine what “classical” music could be. His compositions, such as Music for 18 Musicians (1978) were strikingly minimalist. Using tape loops, and layered cyclical instrumentation, they were unlike any classical compositions before. This desire to eschew all past musical tradition was extremely influential for No Wave artists.

The “missing link” between Reich’s minimalist compositions and No Wave is Glenn Branca. Born in Harrisburg, PA in 1948, Branca relocated to Manhattan in 1976. In New York, Branca assembled electric “guitar orchestras” to make a new strain of harsh, classically-inspired compositions. While based in classical choral, and chamber works, Branca’s compositions utilized distortion, unusual tunings, and harmonics to make something more raucous than any classical pieces that came before. Branca’s releases, such as 1980’s The Ascension are considered as high points of the No Wave movement. While these orchestras inspired the sound of many No Wave artists, they also had a much more direct impact on the scene, directly launching the careers of some of its most prolific guitarists.

Many artists of New York’s avant-garde scene, much like the later No Wavers, began as visual artists, but were inevitably drawn to musical performance. Possibly the most emblematic artist in this vein is Yoko Ono. Although many know Ono as the wife of John Lennon, she independently made a name for herself in New York’s avant-garde scene. Throughout the 1960s, Ono was a major patron of the arts in Manhattan, hosting musical shows and art exhibitions in her Downtown loft. One such exhibition was even visited by Dada artist Marcel Duchamp, whose satirical and utterly strange artworks were a major inspiration for many No Wavers.

Following her marriage to Lennon, Ono became much more involved in the music industry, bringing her experimental tendencies along with her, Her 1970 song “Why” off of Yoko Ono/Plastic Ono Band is a perfect example of this. The song features Ono’s warbly screeched vocals repeating the title “Why,” all over fast distorted guitar riffs. Some of these guitar riffs are so distorted that they register as noise or industrial machinery more than instruments. The repeated lyric additionally reflects the nihilism that pervaded much of Manhattan’s art in the decade, and would continue to into the 1980s. If not having been released nearly a decade early, this piece would be almost indistinguishable from some of Ono’s No Wave successors.

These artists in Downtown Manhattan set much of the groundwork needed to create No Wave. Steve Reich’s complete disavowal of past musical tradition, Glenn Branca’s guitar experimentation, and Yoko Ono’s desire to make music that was noisy like nothing else. There was only one element missing from this witch’s brew: blood-chilling fear. This is where the duo Suicide enter the stage. Formed by Martin Rev and Alan Vega in 1970, suicide created punk utilizing the newest synth technology. Their music was possibly the closest manifestation of the No Wave ethos up until that point. It retained the DIY ethos and anger of punk, but looked to experiment like no one else had done.

Perhaps the band’s most striking achievement is the song “Frankie Teardrop” off 1977’s Suicide. The 10 minute long epic tells the story of a factory worker driven to the point of madness by the industrial slog. Frankie’s job repeatedly pays so little he cannot afford food or rent. In a bout of madness, he kills his family and then himself. This song took the hardships of life in 1970’s NYC and turned them up to eleven. It is possibly the most nihilistic the experimental scene ever got, and no doubt influenced the lyrical themes of later No Wave artists. What makes the song more disturbing is the instrumentation. Harsh synths, with sparse reverberated production surround Vega’s screamed vocals.

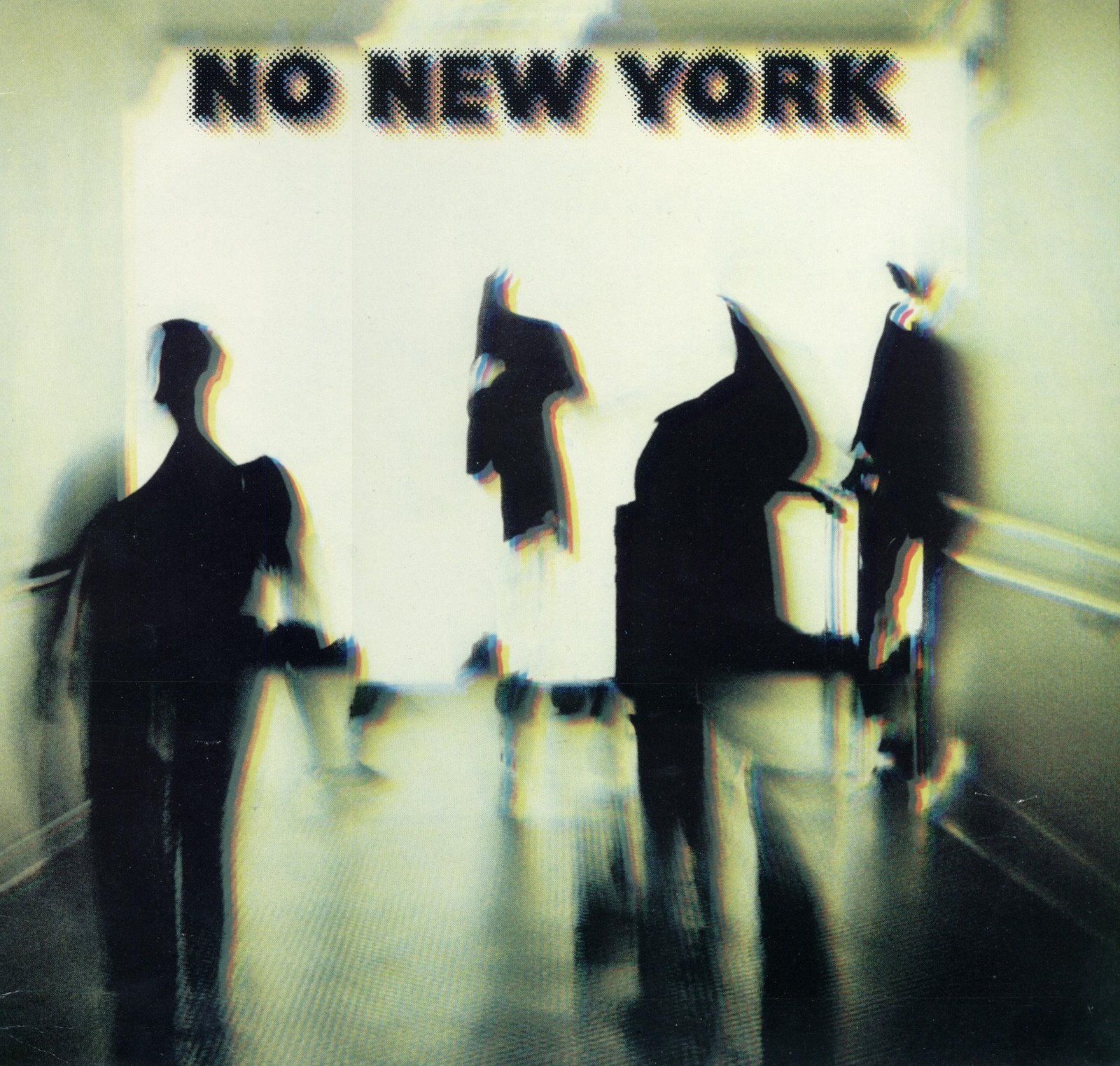

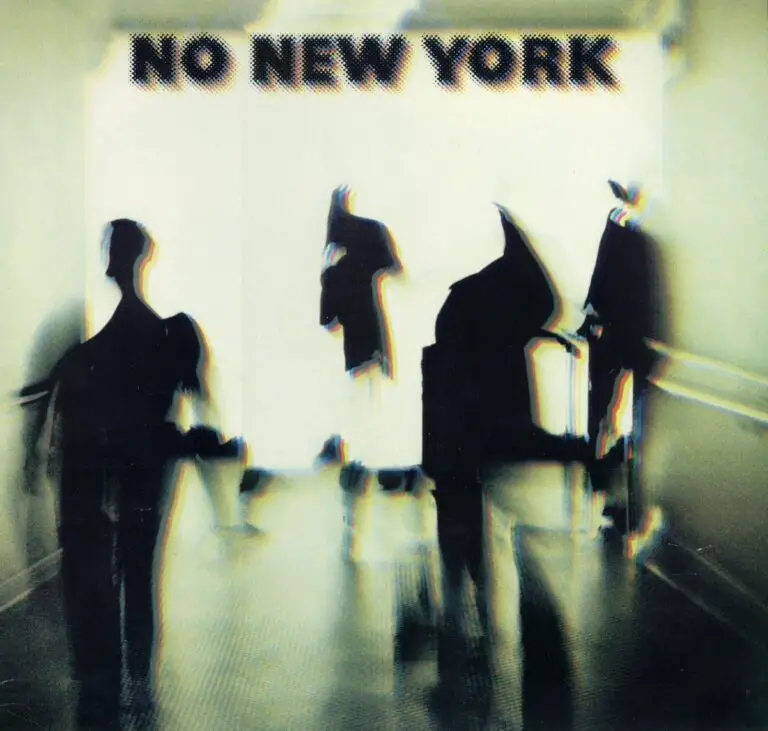

By this point, the building blocks of No Wave were in place, and it just had to be named. The genre would be christened with a 1978 compilation album titled No New York. Legendary musician and producer Brian Eno compiled this album using performances by four of the most seminal bands in the movement. These bands: the Contortions, Teenage Jesus and the Jerks, MARS, and D.N.A. all had wildly different sounds, illustrating how diverse the genre was. Despite this they were all united by a shared community, regularly collaborating at Manhattan clubs like CBGB and Max’s Kansas City.

This compilation also importantly gave a name to the fledgling movement. James Chance of the Contortions credits Eno with the creation of the name “No Wave.” Other pioneers of the movement disagree. Sonic Youth’s Thurston Moore remembers seeing it in CBGB graffiti prior to the compilation’s release, while others credit singer Lydia Lunch. One thing was clear however, that the name reflected a nihilistic spin off of “New Wave.” This name perfectly mirrored the mission of the genre: to be the antithesis of what punk had become.

No New York, while officially creating the No Wave movement, also did a lot of work in ending it. For many, the point of the movement was complete experimentation and freedom of expression regardless of label. The creation of No Wave as a cohesive genre grouped together many bands that had wildly different sounds, who many times did not view each other as colleagues.

Defining No Wave Bands

With the No Wave movement encompassing so many sounds, it is helpful to look at individual artists and how they fit into the movement. By doing this, we can not only trace the careers of some of the movement’s most influential members, but break down what aspects exactly make them “No Wave.”

Swans

Singer and multi-instrumentalist Michael Gira founded Swans in 1982. Since their founding, the band has proven to be one of the longest-lasting and most influential bands to emerge from the No Wave scene.

By 1982, Gira was already a veteran of New York’s avant-garde scene. Gira had previously headed the NYC post punk band Circus Mort until their collapse in 1981. At Swans’ founding, Gira assembled a rag-tag group of No Wavers to form its first lineup. This lineup, featuring Gira on lead vocals and bass, featured Sue Handel on guitar, and Sonic Youth’s Thurston Moore also on bass. This lineup would collapse before Swans could properly record any songs.

Within little time, Swans had recruited Norman Westberg on guitars and were ready to record their 1983 debut LP Filth. Inspired by the decay of New York City, Gira and his bandmates wanted to record something as bleak as their surroundings. Teaming up with Glenn Branca’s Neutral Records, the band began recording their debut in April 1983. Within only one month of recording, the band had laid down 36 crushing minutes that were ready for release.

“I wanted Swans to be ‘heavier’, though. I wanted the music to obliterate — why, I don’t remember! I think it just felt good.”

– Michael Gira, on Filth

Gira recalled in a 2013 interview, his intention in naming the band Swans. “Swans are majestic, beautiful looking creatures. With really ugly temperaments.” Filth is the musical embodiment of this ugly temperament both musically and lyrically. Starting with the instrumentation, Filth is heavy like no other album had ever been. With drumming from Jonathan Kane and Roli Moismann, each song has a pummeling drive that feels like the listener is being thrown headfirst into a brick wall. This percussion was only elevated by Moismann who struck objects around the studio with a metal strap to aid in its pure noise. Westberg’s guitar is also extremely raucous. At most points in this album, it is barely recognizable as an instrument and not just industrial noise.

Michael Gira’s lyrics also aid in crafting an apocalyptic atmosphere to the album. In his lyrics, Gira wanted to paint a picture of Manhattan in decay, criticizing the societal ills he encountered daily. On “Stay Here” Gira rallies against the enslavement of workers by the capitalist system. He sings “Close your fist. Resist. Walk on this line. Look straight ahead,” using this fascistic imagery to bemoan becoming a cog in the capitalist machine. These lyrical themes make sense when seeing the economic state of Manhattan in 1983. For over a decade, New Yorkers had been given economic promise after economic promise, none of which had come true. This song takes the economic frustrations of New Yorkers and releases them in a loud, cathartic explosion.

Intense nihilism and misanthropy mark the lyrics of the whole album. Most evident are those on the track “Freak.” In this song, Gira recounts seeing a rapist walk the streets of Manhattan at night. He uses this story to criticize the moral depravity plaguing the city, as well as larger issues of sexism, and violence for personal gain. He screams the repeated refrain of “You’re gonna murder somebody weak. Strong men win at violence and abuse.” Whether it is the instrumentation or lyricism on this album, they are blunt and forceful enough to kill.

Swans’ early shows were as chaotic as their musical output. To match the sound of their recordings, the band used unorthodox instruments, including whipped sheet metal to add to the noise. This noise was so loud that the band’s shows were frequent targets of police shutdowns due to noise complaints from neighboring properties. In addition to pure noise, Michael Gira treated concerts as physical confrontations as much as performances. Gira frequently stepped on the fingers of anyone touching the stage, and would even jump into the crowd to attack anyone he saw head banging. On top of this, Gira made a habit of shutting off venues’ air conditioning prior to Swans sets. This, naturally made audiences unbearably hot and sweaty. In a 2010 interview, Gira stated that this added a layer of physicality to the band’s sets, making their concerts akin to a sweat-lodge.

While Filth was a testament to the pure force of the No Wave movement, Swans would not remain within the movement for long. Much like the no wave genre as a whole, Swans’ sound evolved to incorporate new genres until it could no longer fall under the label. In 1985, New Orleans-native Jarboe joined the band, adding a new dimension with her delicate and eerie voice. By Children of God (1987) Swans had become a full fledged goth band. With ethereal backing instrumentation and melodic vocals, the band was near unrecognizable. The 1990s saw the band continue down this path, incorporating elements of neofolk, Americana, and post-rock.

The Contortions

Saxophonist James Chance founded the Contortions in 1977. By that time, Chance was only a recent emigre to New York, moving to the city from Milwaukee in 1975. Within those two short years, Chance became enthralled in New York’s free jazz scene: an avant-garde path that put him in league with no wavers.

James Chance and the Contortions’ first release was the No New York compilation, where they were labeled simply as “the Contortions.” From the start, the group illustrated a danceability and willingness to incorporate stylings that were unheard of by other groups in the movement. Chance’s origins in free jazz are clearly seen in the Contortions’ music, with scratchy atonal saxophone being a hallmark of the sound. Bass – usually drowned out in no wave noise – takes a center stage, with groovy bass lines pervading their songs. On top of all of this, scratchy afrobeat guitars reminiscent of Fela Kuti or Talking Heads make no wave fitted for the dancefloor.

“Most of the earlier CBGB type bands, even though I liked a lot of them, I didn’t think were musically very interesting. They hadn’t really gone beyond anything that had come before, because they were still using all the same chords”

– James Chance

The band’s true solo debut would not come until 1979, with their full length LP Buy. This record honed down the Contortions’ sound from No New York. While retaining their trademark mix of abrasive yet funky instrumentation, it provided much sharper production to highlight their music’s edge.

The highlight of Buy is the track “Contort Yourself.” The song is driven by Pat Place’s staccato funk guitar. Unlike their peers Swans, the Contortions took influences from Afrobeat releases like Fela Kuti’s Zombie (1976), anticipating later punk releases like Talking Heads’ Remain in Light (1980). This guitar is accompanied by funk bass, and danceable drums that are as much disco as they are punk.

While significantly more upbeat, this release is not devoid of the nihilism and angst of No Wave. The song features Chance’s scratchy vocals singing about dancing to forget the troubles of the world. “And once you take out all the garbage that’s in your brain. Forget about your future ’cause it’s just, just, just, just too tame, oh.” The command-style chorus recalls previous dance songs such as the twist, but watered down to their bare essentials. Chance doesn’t suggest listeners should dance, but rather commands they “contort themselves,” blurring the lines between voluntary dances and muscle spasms.

Bush Tetras

Following the release of Buy, guitarist Pat Place decided to leave the contortions. This would not mark the end of her music career, as she soon formed Bush Tetras. Alongside singer Cynthia Sley, bassist Laura Kennedy, and drummer Dee Pop, the band would provide an insight into the perspective of women in the no wave movement.

The band is most well known for their 1980 track “Too Many Creeps.” The song retains Place’s funk-influenced guitar, accompanied by an equally funky bass line from Kennedy. The instrumentation, while danceable, is still abrasive, accented by harsh guitar stabs. The highlight of the song is Cynthia Sley’s lyricism, which embodies the paranoia of many New Yorkers. She sings of being too scared to walk the streets because there are “too many creeps.” She can’t even go shopping because she “just can’t pay the price.”

These criticisms of the state of Manhattan’s economy and crime are sung in a monotone, almost apathetic voice. Sley’s vocals embody the wry humor that pervades much of the scene’s music, with listeners being unable to tell if her criticisms are serious or satirical.

The song was accompanied by a 1980 music video that reflects many of these themes. The band plays in a dark studio space that obscures their figures. The video intermittently cuts to scenes of dirty, bustling streets and empty stores, supporting Place’s lyrics.

The band would not last long following the release of this song. Bush Tetras went on to release three more singles in their original run, including “Can’t Be Funky,” which reached No. 32 on the US Club charts. Despite this brief foray into the commercial mainstream, the band did not survive. In 1983, both Kennedy and Pop left the group, ending the band’s original run.

Sonic Youth

Sonic Youth were possibly the longest-lasting and most influential band to emerge from Manhattan’s No Wave scene. With their melodic, pop-influenced take on noise rock, they helped push the avant-garde into the mainstream. As a result of their experimentations, modern genres of alternative and indie came into existence.

Guitarist Thurston Moore and bassist Kim Gordon founded Sonic Youth in 1981. Gordon, like many members of the No Wave movement, was not a musician by trade. Following graduation from Los Angeles’ Otis College of Arts and Design, Gordon relocated to NYC to pursue a career in the fine arts. Much like many of Manhattan’s visual artists she soon took great interest in the musical experimentations occurring around her, and decided to pick up the bass guitar.

Thurston Moore, on the other hand, was in the music scene from the get-go. Raised in Bethel, CT, Moore consumed a diet of classic rock throughout his childhood. By the late 1970s, Moore’s interest had shifted firmly towards punk rock. He recalls, “it was David Johansen to Patti Smith to John Cale to the Ramones…” By 1977, Moore had moved to Manhattan to be at the heart of the punk scene. Following stints in hardcore bands, Moore joined Glenn Branca’s aforementioned guitar orchestra.

It was in Branca’s orchestra that Moore met fellow guitarist Lee Ranaldo. Ranaldo – a Long Island Native – moved to Manhattan following a stint at SUNY Binghamton studying film. Ranaldo admits that his studies mostly consisted of doing drugs and playing guitar. With the addition of Ranaldo, the band had their stable core, which would be accompanied by a rotating host of drummers and multi-instrumentalists.

Sonic Youth’s first two full-length LPs are defining releases of the No Wave movement. Their debut Confusion Is Sex (1980) is equal parts noisy nihilism and odes to their influences, both past and present. Besides a cover of the Stooges’ “I Wanna Be Your Dog,” the album features mostly original compositions, and collaborations with other No Wavers.

Track 6, titled “The World Looks Red” is possibly the greatest of these collaborations. With lyrics from Swans’ Michael Gira, the song embodies a feeling of paranoia and alienation that perfectly encapsulates the underlying attitudes of No Wave. Moore sings “The weight of my body is too much to bear. The memory drained. The life from the doll.” This track also marks the beginning of Moore’s guitar experimentations. The song features whirring instrumentation that almost sounds like a distorted synth or organ. The instrumentation is actually the result of Moore jamming a broken drumstick into the strings of his guitar. Moore would continue these experiments on later releases.

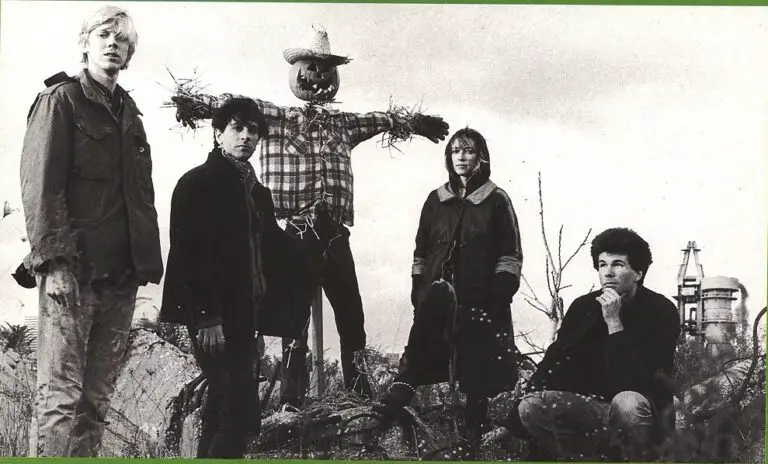

The Band followed up their debut with 1985’s Bad Moon Rising. Sonic Youth recorded the album throughout 1984 in Gowanus’ Before Christ Studios. The studio sat along the Gowanus Canal, a waterway contaminated with industrial waste. Outside the studio, gangs and stray dogs roamed the streets. This dystopian recording environment influenced Sonic Youth to record their most apocalyptic sounding album to date. The album art reflects these themes, featuring a scarecrow with a flaming pumpkin head overlooking New York City.

Bad Moon Rising saw Sonic Youth experiment more with musical texture, rather than sheer noise, incorporating more dialed back musical passages. One example of this is track 3, titled “Society is a Hole.” This track retains some of the lyrical themes of earlier No Wave songs, bemoaning conformation to societal norms. The difference with this track comes from its instrumentation. It features droning guitars that slowly build upon each other. As the song progresses, harmonics and distortion are added. As a result of this instrumentation, the song is a slow burn rather than an all-out assault like their past work was.

The album, however, is not devoid of the noise rock that marked Sonic Youth’s debut. The highlight of the album is the seventh track, titled “Death Valley ‘69.” This track is a collaboration with No Wave icon Lydia Lunch, who provides screeching backing vocals. A bloodcurdling scream from Moore kicks off the song, only adding to its apocalyptic atmosphere. The song features dissonant fuzzed-out guitars that propel the song forward. One thing that sets “Death Valley ’69” apart from other no-wave songs is its lyrical content. While the track does not tackle the decay of New York City, it still embodies the genre’s trademark misanthropy. The song’s sneering lyrics retell the story of the Manson Murders in 1969 Los Angeles, and exude an overall disgust with humanity.

The bands’ early live performances matched the feverish intensity of their studio albums. Much of this intensity came from Thurston Moore and his dedication to achieve new guitar tones regardless of the cost. The band’s original drummer Richard Edson recalls a practice in his apartment where Moore especially suffered for his art. Edson remembers seeing red spots appearing around the room and on his drums. As it turns out, Moore’s guitar broke, leaving exposed metal sticking out. As Moore played, he tore apart his hand on the metal, sending blood flying across the room. Edson later recalled thinking it was “pretty cool that he’s so committed that he’ll play right through any kind of pain and bodily injury.”

The band’s live shows also allowed them to develop their trademark sound. One trademark of Sonic Youth was their use of alternate tunings. Not wanting to spend ages retuning their instruments between each song, the band members bought cheap guitars to keep in different tunings. These guitars, however, would quickly go out of tune during performances, only adding to the raucous sound of their music. In addition to this, Moore began to explore musical timbre in these live shows, using unorthodox equipment to achieve new songs. Moore would hit his guitar strings with a drumstick, and even jam a screwdriver into his guitar to achieve new sounds, pushing the limits of how guitars could be used as instruments.

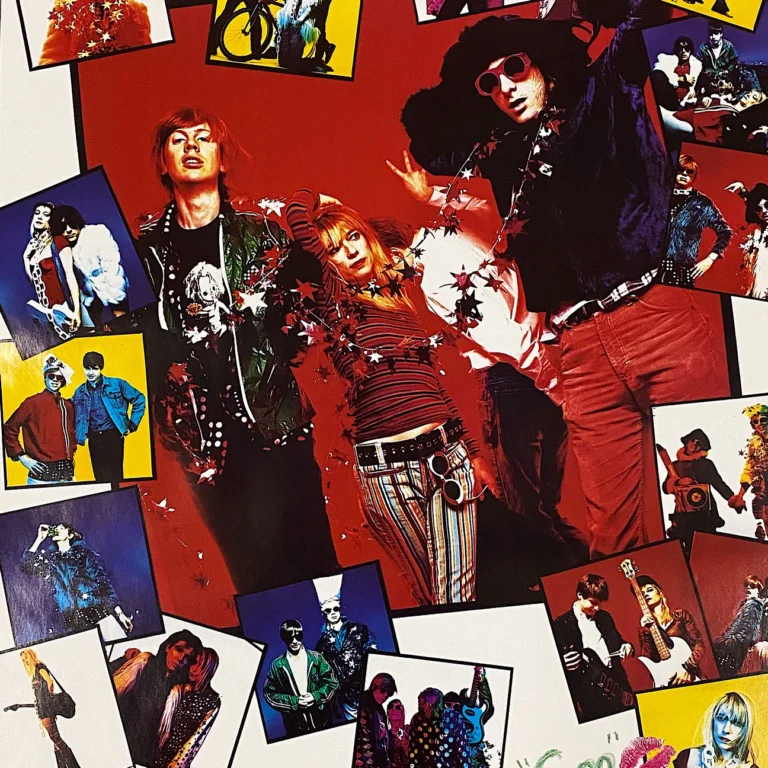

Sonic Youth was unlike many other members of the No Wave scene because they had a genuine love for pop music. They especially loved one singer who emerged from New York’s art scene: Madonna. Thurston Moore recalls Madonna’s presence in the city’s music scene, blending aspects of new wave, hip hop, and latin music. Moore also claims that Madonna was in an early no wave band with Dan and Josh Braun, who would go on to be founding members of Swans. Regardless of her No Wave bona fides, Sonic Youth looked to Madonna for influence, increasingly incorporating pop melodies into their songs.

This influence is most clearly seen in 1988’s The Whitey Album, by the band’s side project Ciccone Youth. The project name and cover both reflect their admiration for Madonna, with Ciccone being her surname. Additionally, the album cover features a zoomed in, distorted photo of Madonna’s face. On top of Sonic Youth, this album features contributions from Minutemen bassist Mike Watt, and Dinosaur Jr. guitarist J Mascis. The centerpiece of this album is a reimagining of Madonna’s 1985 hit “Into the Groove.” This cover manages to maintain its pop catchiness, while being sludgy and industrial.

As the 1980s progressed, Sonic Youth began incorporating influences beyond just pop. The band’s songs became increasingly melodic, as they absorbed aspects of post-punk, classic rock, and noise to form a new fledgling genre. The genre was initially coined “College Rock,” due to its frequent airplay on college radio stations. However, by the dawn of the 1990s, it became known simply as “alternative.”

Sonic Youth’s alternative output from the 1980s illustrated a growing maturity in their sound. Albums like Sister (1987) and Daydream Nation (1988) are a perfect blending of noise and melody. While Moore and Ranaldo’s dissonant guitars still pervade much of their songs, their composition and lyrical themes illustrated a growing maturity to their sound. With songs like “Schizophrenia” that tackles mental health, and “The Sprawl,” with its sci-fi influences, the band was willing to cover themes no other No Wavers would. The band even wrote catchy youth anthems, such as “Teen Age Riot,” a far cry from their no wave roots.

Sonic Youth continued to release albums until their breakup in 2011. This breakup coincided with the divorce of Moore and Gordon, who had been married since 1984. As Gordon recalled about Moore in her 2015 autobiography Girl in a Band “He was an adolescent lost in fantasy again, and the rock star showboating he was doing onstage got under my skin.” While the band has remained on hiatus since 2011, its members have each helmed a number of solo projects.

Legacy

As it turns out, No Wave was a rather short lived movement. As seen with Swans and Sonic Youth, the movement had largely disappeared by the mid 1980s as bands updated their sounds. Many bands, including the aforementioned Bush Tetras did not survive the decade, disbanding not long after their founding.

Despite its short lifespan, No Wave left a lasting impact on the music industry. The boundary-pushing sounds of No Wave bands inspired countless genres, ranging from metal to alternative. Swans’ harsh wall of noise was especially influential on new styles of industrial and metal emerging in the 1980s. Justin Broadrick, founder of the pioneering industrial metal band Godflesh, recalled Swans’ influence on his band. “It was non-genre-specific, with a total lack of baggage… purely abstract, surreal, and violent…Swans paved the way for me.”

Sonic Youth proved to be the most influential band to emerge from the No Wave movement. As the 1980s progressed, the band’s success only continued to increase. By 1990, Sonic Youth was at the head of the alternative rock movement, headlining tours across the world. The band’s largest step towards success was their 1990 album Goo. The album track “Kool Thing” shot to 7 on Billboard’s Alternative Airplay chart and launched a 1991 European tour. This tour proved to be especially important for the history of alternative and rock music. For their opener, Sonic Youth selected an up-and-coming band from Washington called Nirvana. Along the tour, Nirvana played new songs like “Smells Like Teen Spirit,” which launched them to superstardom only months later on their album Nevermind.

For only a brief moment, a community of young misfits took over Manhattan’s underground music scene. These young artists tackled the issues of urban decay and violence they experienced every day, all while pushing the boundaries of what music was. While No Wave never had a unified sound, it did have a unified community of artists who performed and recorded with one another. As pop critic Roy Trakin said, “They really have little in common musically except their stubborn belief in the uncompromising stands they’ve taken.” These misfits, while starting in the underground, soon propelled their brand of alternative to the top of the charts, changing the music landscape as we know it.

The post No Wave: Welcome to Fear City appeared first on NYS Music.